Welcome to another episode of the History Islands.

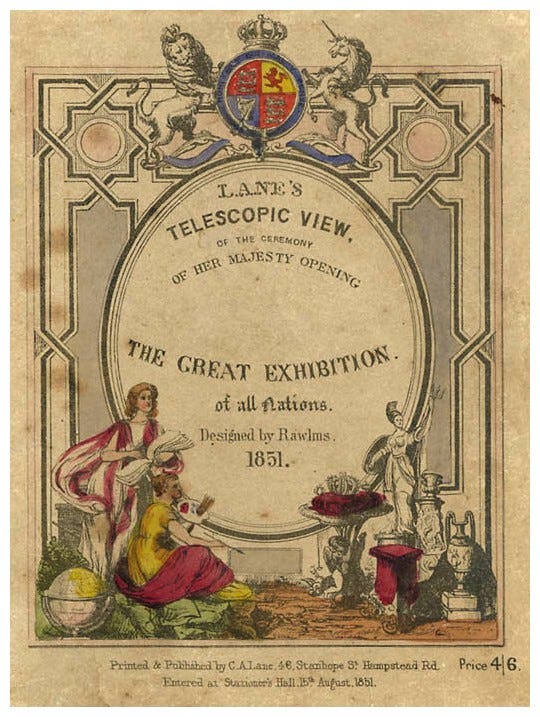

Today we meet Jersey’s Colonel John Le Couteur, who is attending the opening of the Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, London, in 1851. The Channel Islands occupy a prominent place at the event.

The world is changing. Prince Albert, the scion of the Victorian age, puts it best – “the unity of mankind is within reach”. Technology drives his optimism. “The distances which separate the different nations and parts of the globe”, he declares, “are rapidly vanishing and we can traverse them with incredible ease; thought is communicated with the rapidity, and even the power, of lightning”. The telegraph, the penny post and the maritime arteries of empire are binding the world together, and Jersey is deeply enmeshed in the web. Indeed, the first pillar boxes in the British Isles will open in St Helier in 1852.

To celebrate the new era of global seaborne trade, the Prince Consort has called upon the world to showcase its greatest treasures in London. They call it the “Great Exhibition”.

Colonel John Le Couteur

1st May 1851

An emissary from the future has landed here at Hyde Park, and Queen Victoria is riding out to greet it. This crystal cathedral is an extraordinary glimpse of tomorrow: an astonishing ice palace, carved from nine hundred thousand square feet of glass, rising out of twenty-six acres of prime London parkland.

As a proud Jerseyman and aide-de-camp to Her Majesty, it is an honour to witness this day. I stand here at the opening of the 1851 Great Exhibition: a visionary project to showcase the finest works of human and natural creation. Prince Albert, its instigator and architect, says it will provide “a living picture of the point of development at which the whole of mankind has arrived”, and a worthy inspiration for further innovations. He has struck the mark.

I can scarcely imagine that six million people – almost a quarter of the population of Great Britain – will be mesmerised by the show before the year is out. Every nation has shipped its most exquisite works here, vying to showcase the most sublime craftsmanship, the fastest machinery, the most serene art. And Jersey and Guernsey, as the Crown’s oldest bailiwicks, occupy a prime position at the very heart of this magnificent new Crystal Palace.

As the Exhibition opens on May 1st, thirty thousand visitors cheer the young Queen. Secrecy has shrouded the great project for months; behind barriers, two thousand men and four steam-pumps have toiled away unseen. We could only imagine the marvels that they had conjured. Now the veil has at last been lifted, and the astonishing scale of the works are revealed to the world. The Exhibition occupies almost a million square feet, and the galleries alone stretch for almost a mile.

The immediate sense of light and space proves somewhat alarming, and many visitors are left dizzy, unsettled by the shock of the new. The official Catalogue will note a “sense of insecurity, arising from the apparent lightness of its supports as compared to the vastness of its dimensions”. Even the original great elms from the park have been incorporated within the glass, like strange arboreal specimens from the past, their arms brushing up against the soaring ceiling. At the Exhibition’s hub stands Osler’s Crystal Fountain – a translucent masterpiece shooting twenty-seven feet of water. It is built from four tons of pure crystalline glass, and the world has seen nothing like it.

Queen Victoria advances to declare the Exhibition open, to the strains of the National Anthem. I am lost in a sea of dainty bonnets and tall stovepipe hats; one onlooker amidst the tens of thousands overawed by this feast of treasures. After all the cheering, there is a profound silence, as we recite the choruses and prayers. Thirty thousand voices abruptly fall still, and I feel as if I am falling into a deep well.

The Archbishop of Canterbury concludes his address. As Handel’s angelic ‘Hallelujah’ chorus resounds throughout the cavernous palace, I have a strange sense that we stand present at the creation, at the start of something profoundly new. We have been granted a glimpse of the world to come.

The Queen departs. As if the heroes of History itself have come to pay homage to the future, the ancient Duke of Wellington follows in her train. The poor old chap looks very feeble, but still he touchingly offers a supporting arm to his old comrade and sparring partner, Lord Anglesey. The two grand old men survey the miracles unfolding all around them. Instead of cannon fire, they walk into a battery of spontaneous and heartfelt applause.

Truth be told, so many of us had feared the opposite - an angry republican mob, or worse. The shadow of the Hungry Forties is not so long past after all. Yet the worst transgression I witnessed today was from an enthusiastic royalist, who had shinnied up a high platform to catch a better view of the Queen. He was soon ushered down with an indulgent smile. Far from some towering Babel of confusion, this Exhibition seems the very model of decorum and order. The crowds swarm, like bees; bustling hither and thither, but in a sentient and ordered fashion, churning out the sweet honey of Progress. I have a season ticket to the building and will visit again and again.

As the weeks go by, I am delighted to note that the peace and order continues even on those days when tickets are cheapest. In fact, the gentry, shelling out their half-crowns for plum viewing times, are not nearly so polite as the ordinary Londoners.

The exhibits are marshalled into four categories – Raw Materials, Machinery, Manufactures and Fine Arts. The world’s treasures have been corralled here. Yet, in my opinion, the industrial wonders surpass all. Electric telegraphs even enable us to summon carriages directly to the gates to meet us – no need to wait in line for a hansom cab!

When I was a young boy, a galloping horse was our fastest carriage. Now we behold locomotives that can devour seventy-three miles in a single hour. Imagine my own joy and surprise as I tested a wonderful new quill that actually holds a reservoir of ink inside it – and it writes beautifully. No more need to scrabble around in inkwells after every second stroke! Mark my words: they call this device a “fountain pen”, and I believe it is going to make history.

Colonel Le Couteur was not the only visitor who left thunderstruck. The Great Exhibition seems to have sparked euphoria in many; a sheer intoxication with the power of technology. The great writer Charles Dickens himself visited twice but withdrew, overwhelmed by the dizzy kaleidoscope of sights. Yet for most, the house of wonders proved as hypnotising as the recent California gold rush. It was quite simply, in Colonel Le Couteur’s words, a “fairy palace”.

The Great Exhibition was the fruit of the vision of two men of unbounded and immense energy - Henry Cole, reputedly the inventor of the Christmas Card, and thirty-one-year-old Prince Albert himself. The objective was Utopian - to foster global peace, to beat swords into ploughshares. In the Channel Islands, poised on the front line of clashing kingdoms since time immemorial, the message was well received.

Colonel Le Couteur overcame his initial misgivings and decided to embrace the project. He would eventually visit the Great Exhibition no fewer than fifteen times. In his capacity as a scientist and founder of the Royal Jersey Horticultural and Agricultural Society, he personally exhibited over a hundred specimens of wheat from his gardens in St Brelade. Seven of them proudly bore the name “Jersey”. Mens’ and Ladies’ Committees in both Islands were established, and parish Constables even called house-to-house to seek funds.

After a short display in Gloucester Street in St Helier, the exhibits were shipped to London, with Henry Cole, the effervescent dynamo behind the Exhibition, personally escorting them to their stand. Jersey and Guernsey occupied an enviable position on the north side of the nave, next to Ceylon and India, near the Crystal Fountain at the centre of proceedings. The red saltires of Jersey hung majestically above the stand, with the leopards of both Bailiwicks prominently displayed on flags above.

The stand, built by George Clement Le Feuvre and William Stead, was designed to showcase the beauty of the Islands. It featured a plentiful array of traditional woollens. There were decorative shells from Herm and samples of Guernsey Blue granite, the stone used on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral.

Jersey butter-making was also demonstrated daily during the Exhibition. Le Couteur recorded in his diaries that one churn produced 21 lbs 2 oz of butter in just two minutes, and another churned 28 lbs in just four and half. The latter portion he gifted as tribute to the Queen, and he personally called at the Palace the next day to ensure it had been safely received.

A Channel Islander provided one of the greatest technological marvels of the Exhibition. The crowds were mesmerised by Guernseyman Thomas de la Rue’s “Patent Envelope Machine”, which occupied its own special display. In a series of elegant and balletic mechanical moves, it cut, folded, gummed and forwarded thousands of envelopes an hour. The machinery was astoundingly productive, and as graceful as a swan, yet it was operated by just two boys.

One Jersey work of art was even honoured by an illustration in the official 1851 Great Exhibition catalogue. While lamenting that “the contributions from our fellow countrymen in the Channel Islands are comparatively few”, it praised “a CHEFFONIERE, or sideboard, manufactured by Mr G C LE FEUVRE, of Jersey; it is made of oak, a portion of the wood being the produce of the island; the designs in the compartments are worked in tapestry”. The emblems of England, Scotland and Ireland adorned embroidered panels, sewn by Mrs Le Feuvre.

The upper section of the cheffonière depicted King John, surrounded by rebellious barons and bishops, poised to sign the Magna Carta. One bishop wields a patriarchal cross; another bears a mitre. Alas, this section did not meet the Catalogue’s refined critical standards, so was not deemed worthy to be illustrated. Still, Jersey’s local woodworkers had gone head-to-head with the world’s pre-eminent artisans and had proved their worth.

The Great Exhibition shone like a supernova burning in the sky, drawing the world to it for a season. Yet the fairy palace that shimmered at daybreak would not last. This glittering temple of materialism finally closed its doors in October 1851. After six months, it was relocated to the heights of Sydenham in south-east London, where it would eventually burn to the ground, in a darker, sadder century. The charred remnants were swept aside, along with the hopes and dreams of the Victorian age. Only the name endures.

Yet the Exhibition was a signpost to the future, fulfilling the extraordinary prophetic vision that Prince Albert had decreed in his original speech: “The Exhibition of 1851 is to give us a true test and a living picture of the point of development at which the whole of mankind has arrived in this great task, and a new starting point from which all nations will be able to direct their further exertions”.

Albert would die tragically young, but he left us Albertopolis, the extraordinary cultural wealth of South Kensington’s museum quarter. His golden statue presides there to this day, clutching the Exhibition Catalogue. Inspired by his legacy, little Jersey would go on to hold the Channel Islands Great Exhibition in 1871 at the Victoria College Showground.

Yet as the Great Exhibition at Hyde Park closed its doors in 1851, the triumphant Le Feuvre and Stead faced a more prosaic dilemma on returning home to Jersey. They had incurred substantial expenses in the project; how best to recoup the funds? It was strictly against Exhibition rules to sell the display products, so they devised a lottery.

The first prize would be the ornate cheffonière itself, valued at the princely sum of £350. Alas, the States of Jersey took umbrage and intervened to scupper their plans. The Lottery was cancelled. So, what became of this exquisite piece of craftsmanship, viewed by millions, and arguably one of the most celebrated works of art in Jersey’s history? It appeared to vanish without trace. They say it still stands somewhere in a grand English house, holding fast to its secrets, a story waiting to be told.

This story is an extract from my second book, Jersey: Secrets of the Sea, which is available on Amazon and in Waterstones, WH Smith, the Jersey Museum and the Harbour Gallery in Jersey. © Paul Darroch 2024.

Music: Chariots by Gavin Luke courtesy of Epidemic Sound. Images: Wikimedia Commons.