I’m Paul Darroch, and welcome to another episode of the History Islands. This is the true story of Louisa Journeaux, and it’s taken from my second book, Jersey: Secrets of the Sea.

It is the Spring of 1886. Queen Victoria is nearing her forty-ninth glorious year on the throne, and the ageing William Gladstone is embarking on his third ministry. In New York, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty is being completed; in France, Gustave Eiffel is promoting his radical designs for a quite astonishing tower. Yet as the new year dawns, Jersey finds itself in the grip of turbulence, of a banking crisis. Hard on the heels of the Jersey Banking Company’s collapse comes the shocking news that, as a result, the venerable Charles Robin Company itself has been plunged into bankruptcy.

In these unsettling times, it is curious that the tragic story of an ordinary Jersey girl gripped the imagination of Jersey press and people alike. Yet the unsettling tale fulfilled so many of the sensibilities of any Victorian narrative, offering original sin, a damsel in distress, a dramatic court trial, a terrible ordeal and a surprising deus ex machina resolution. Yet this quintessentially Victorian tale belongs in no penny dreadful or Dickens periodical. It is the astonishing true story of Miss Louisa Journeaux, a guileless young lady from St Clement.

April 1886

“We are all just a slip away from oblivion. Any of us can fall in an instant. Consider our dear neighbour: a precious young lady, a churchgoer no less, who paid a terrible price for a moment’s madness. She placed her very life, her trust, into the hands of a young man she barely knew, and he threw her into the abyss. Remember her fate tonight and pray for her soul”.

The preacher wielded his words like sharpened knives, letting their echoes clatter down onto the flagstones. Every syllable cut deep. The congregation cowered, recoiling in shock, for they knew this tale all too well. The whole Island had grieved for a month now, speaking of little else save the heart-rending story of Miss Louisa Journeaux, of St Clement’s Parish, presumed dead.

Louisa’s tragedy was the shame of the Island, the anguished lament of newspaper correspondents, the daily prattle at the Town Pump. True, the Honorary Police were yet to find any trace of a body, merely the remnants of her pathetic, broken parasol. Yet it would surely be only a matter of time before her swollen corpse came in with the tide.

Everyone knew the dreadful mistake that poor sweet girl had made. Her final moments were known only unto God, but the outcome of the tragedy was clear to all. Louisa Journeaux would never be coming home.

Louisa Journeaux

St Helier, Jersey

Sunday - April 18, 1886

It was Palm Sunday, the day when Jesus rode his donkey into Jerusalem long ago. The promise of Easter was just around the corner, and I had bought some lovely greeting cards, showing fluffy chicks pulling fairy carriages. Unbeknownst to my younger cousins, I had also scoffed a tray of Fry’s gorgeous chocolate eggs, but I would be sure to replenish my supplies before the Easter Egg Hunt itself.

My cousin Julia and I had dozed dutifully through Evensong, but it was such a beautiful evening, that kind of clear Spring day in Jersey when the sky is simply ablaze with colour. It seemed far too early to retire to bed. True, I am twenty-two years old now (whisper it softly!) but Julia and I are still little girls at heart; we simply fancied another adventure.

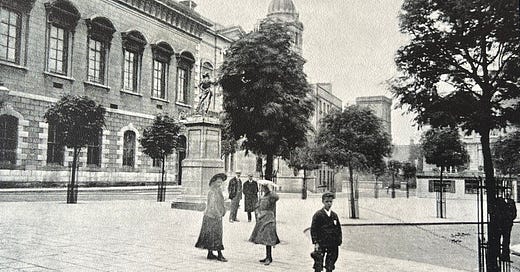

After church, we strolled down through Royal Square, where we had seen all those handsome and dashing soldiers on parade – it must have been five years ago - to mark the centenary of the Battle of Jersey. Of course, this being a Sunday evening, all the shops were boarded up now, their shutters drawn down. The brash advertising hoardings advertised the fine merits of Perrot’s print-shop to just a few passing pigeons. And as we walked down past the Public Library, a peal of gorgeous birdsong burst around us.

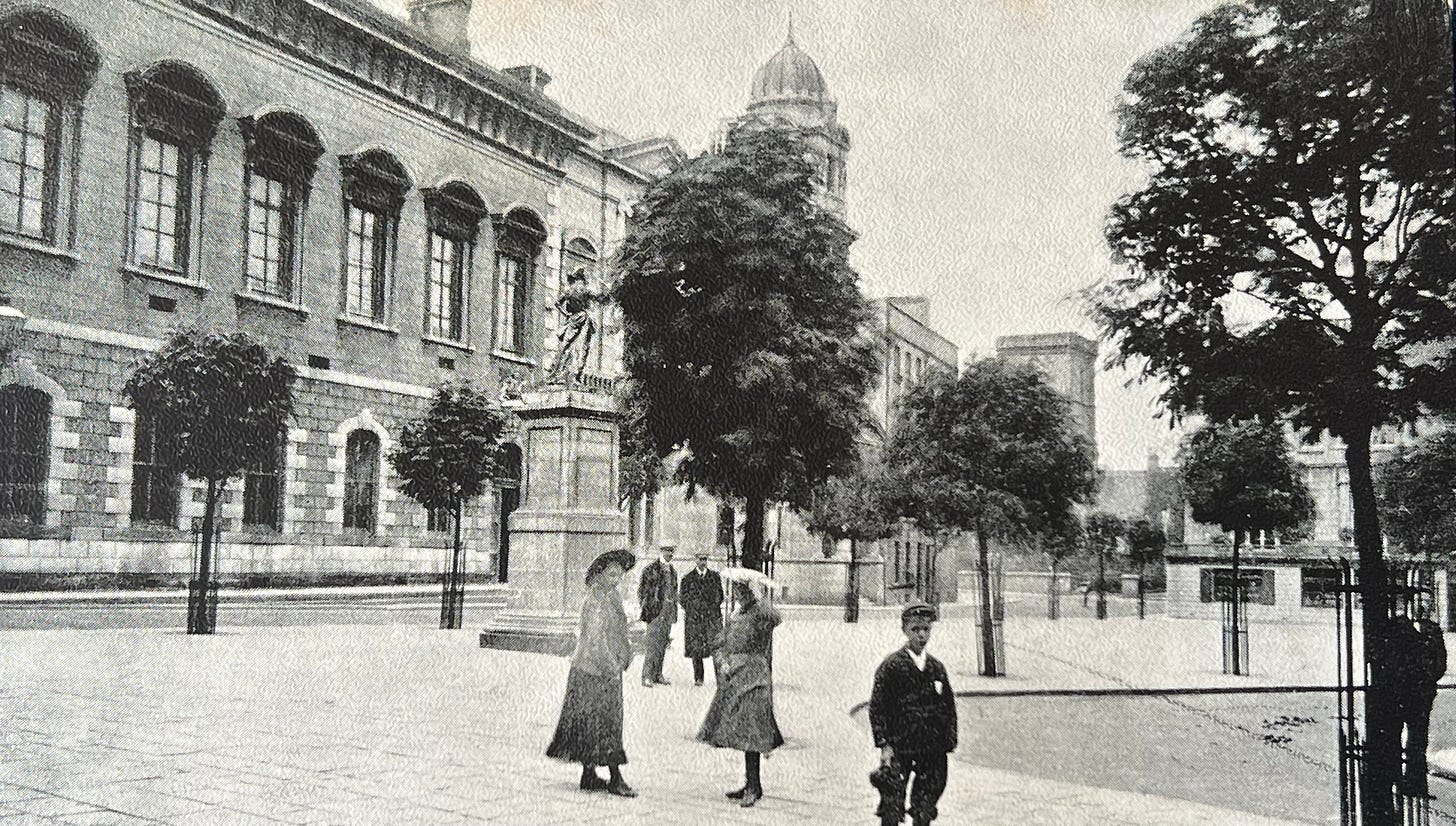

It promised to be a glorious sunset. We soon broke out onto the Weighbridge and were greeted by a forest of tall masts. It seemed to me that each one was whispering salt-tanged promises of faraway harbours, and every ship had a secret to share. My heart began to sing.

Caught in this haze of delight, we were strolling down to the waterfront with our parasols, when two young Frenchmen caught our eye. They were larking around near the Westaway Memorial, dancing right in front of the railway terminus, and with typical Gallic bravura, they brooked absolutely no delay in introducing themselves to us.

The eldest I recognised at once; M. Jules Farné, a young gentleman I had already laughingly conversed with a few times at the shop counter. He was a dapper hairdresser with a wayward smile and an accent that soon enough melted my heart. “Would you like to join us for a drink of cocoa?” He regaled us with delightful tales of Paris; of Spring in Montmartre, of artists and cherry trees, and the astonishing ice-white basilica they are apparently building there, high above the city. I was hooked like a fish.

His best friend, M. Radiguet, who was a little less bold, lavished his courtly attentions on my cousin Julia. We all laughed and joked together, and shared steaming cups of hot chocolate as the rays of the evening sun lapped down over the Weighbridge. The night was balmy, and the moon was rising high above the Fort. Then suddenly a madcap notion darted into our evening like a sparrow falling in the square.

Jules proposed it so flamboyantly, so poetically; and I was at once bewitched. “Let us take to the water”, he told me. “Let us drink in the moonlight together. It is the French way. I will be your captain. I will take you out upon the waters, and then I will lead you home”.

Two days later.

Channel Approaches, west of Jersey

Tuesday - April 20, 1886

The raw anger of the Atlantic slams with the force of a cudgel against Louisa’s matchstick boat. She is thrown hard by the shock of the breaking wave, and rolls like a rag-doll across the timbers, grasping at them for sheer life. She is too numb to cry.

Louisa is far from home now, dozens of cold nautical miles away from land. Stripped of its oars, her little skiff is casually tossed by swells the size of hills; is cast like a child’s wooden toy over a sea-crest, then spins away to float gently in its sluggish wake.

In these brief moments of respite, Louisa finds herself working like an ox, despite her utter exhaustion, to bail out the saltwater that is slowly drowning her craft. She scoops it out with Jules Farné’s hard felt cap, the last reminder of the would-be lover who had left her to die.

The Atlantic Ocean is an unforgiving place, where sky and sea merge, and gut-churning swells drench and batter her boat. Yet there is a strange beauty in this void. In the icy stillness of the night, the stars hang as close and bright as lanterns, blazing across the skies from pole to pole. No-one else is here to witness the astonishing sight. On her first night at sea, Louisa briefly glimpsed the Southampton steamer cutting up the horizon; since then she has been utterly alone.

Everything in this world is drenched to the core, corroded by a seamless curtain of sea and rain. Her dainty ladies’ parasol was lost in her first night on the water; now she faces the second night with no shelter at all. Louisa’s Sunday best, her church finery, are mere sodden rags and a heavy chill has started to gnaw into her bones, turning her legs to lead.

Louisa’s raging thirst is slaked only by mouthfuls of rainwater, but she is still feverish, driven to delusion by the pummelling tides. Somewhere deep inside, Louisa is preparing to die. Her thoughts are flying away with the seabirds across the black ocean, and her mind is slowly turning as numb as her hands. For a fleeting moment, she half-remembers the comfort of her father’s cosy fireside; but tonight, her home feels as distant as the icy moon.

A sorrowing pall of grief hangs over that childhood home, Elder Cottage in St Clement. No-one in the Parish can forget the shock of that awful first night when her cousin Julia returned; shrieking like a demented banshee, and alone. Neighbours clucked behind curtains when the Centenier rode by at daybreak; now parishioners cross themselves in sympathy as they pass the smitten house. Louisa’s ageing parents are cloistered within, riven by grief, confined to their beds. As news spreads, a pulse of anger is seething across the Island; more than a handful of hot-tempered young lads are already thirsting to beat Jules Farné to a pulp. To keep the spectre of mob rule at bay, the wheels of Jersey justice are grinding forward with unaccustomed speed.

By now Jules, the sometime rowing boat captain, is impounded in the St Helier police cells, in the stern custody of Centenier Le Gros. He had been found clinging like a limpet to the pier-head, half-drowned and blathering. Under police interrogation, the facts have started to tumble out like a haul of fish; slippery, evasive and thrashing with obvious contradictions. Yet with the help of the distraught witnesses and with the shadow of the gallows lurking in his fearful imagination, the authorities slowly gather a clearer picture of the night’s tragic events.

It had all begun with such an innocent fancy. Jules confessed he was desperate to romantically impress Louisa, and despite his sketchy nautical skills, he was confident he could capably handle a little rowing boat in a sheltered harbour. So, the young Frenchmen hired skiffs from portly Mr le Feu; Louisa and Jules would share one of them. The boat-keeper warned this was foolhardy, that night would be falling soon, but the youths were bothersome and insistent, so he reluctantly trousered their coin.

It was already a quarter past eight, and the dying sun was slipping down behind Noirmont, when the two skiffs finally slipped away from their moorings. At first it was a jaunt, a sheer lark, punctuated by giggles and banter. Louisa and Jules began to drown in each other’s eyes. At sea, any prying gossips would scarcely see the couple nudging dangerously closer. The sky glowed a soft and gentle pink, with dark blue cotton-clouds painted as if by hand onto the golden sunset. Seagulls cawed and circled overhead.

They soon made the pier-end, but caution be damned: the water was as smooth as a millpond. It was an unseasonably humid night and Jules, drenched in perspiration, loosened his tie a little and unbuttoned the upper buttons of his shirt. The skiff glided silently across the water, and Louisa was soon hypnotised by the rhythm of the oars. He would give her one last adventure, he promised. He would race out to the Castle and complete a final glorious circuit under the moon, then ferry her safely home.

The last magical lap at sunset unfolded in a shared dream. Louisa was besotted with this oarsman’s skill; he was clearly no novice. Then the first stars nuzzled out from behind the night-clouds, dancing a chorus of blessings. Jules pulled the skiff back into the embrace of the Victoria and Albert piers. Now was the time. He swung both oars in, boldly grasped her milk-white hand and moved in ever closer, drawing her towards a moonlight kiss.

“Then I saw that there was a way to hell, even from the gate of heaven…” As he did so, his concentration lapsed. The first oar slipped from its rowlock and splashed noisily into the harbour. Jules swore in French and attempted to turn the boat, but he was fumbling and distracted, and the second oar followed it under. The tide was now ebbing fast out to sea, tugged by the magnetic pull of the moon. The moment called for action. Jules deftly leaped into the sea to chase the oars, but emerged spluttering like a fish, empty-handed. He tossed his felt cap back into the boat, then vanished. The tide was relentless now, and his screams were lost in the rising darkness.

Louisa was gone. Her boat was hurtling away fast on a brutal ebb tide. She screamed back – for Jules, for help, for deliverance. No-one came. She screeched again, until her throat was blood-raw and her eyes stinging with tears. No-one heard. Then the glittering lights of St Helier receded as if in a dream, with the Weighbridge lamps a last painted flourish of yellow in a canvas that was fast rolling up behind her.

Within minutes, the landward horizon was a smear of black coal, and the last points of light had utterly faded. Louisa was viciously dragged out to sea by the raw power of the tides, as if tied to a runaway horse, or carried away on a locomotive with no driver. Stinging drops of rain started to pelt down like daggers. She raised her flimsy parasol to counter them, and it shredded in minutes. Then everything faded to black, and her bearings dissolved in the darkness. Her world had shrivelled to the sodden innards of an open boat. Her last cries muffled by the rainstorm, and far from any shore, Louisa fell away into the night.

The Royal Court was packed to the gills on the day the prisoner was dragged in for his trial. The Crown’s formal charge struck the young man with the force of an oar to his skull. Jules Farné, had “by his neglect and imprudence, caused the death or disappearance of Louisa Journeaux”. A parade of witnesses was called forth to testify. A broken parasol had been found washed up on the rocky headland at La Collette, and Mr F. Journeaux formally identified it as belonging to his beloved daughter Louisa. The press summarised his testimony: “Last Sunday his daughter attended divine service, and afterwards went for a walk. He did not know the accused; but was aware his daughter was acquainted with him”. Then Miss Julia Wiltshire, dressed in black, gave her own solemn account of the fatal rowing trip.

The rival Advocates jousted like medieval knights, sparring with brutal parries, rhetorical lunges and the occasional chivalrous flourish. The prisoner had given two separate, conflicting accounts; but Advocate Le Gallais, defending, “maintained that the whole thing had been a deplorable accident”. His words carried weight. In the end, the Magistrate determined that there was insufficient evidence to convict the accused. Jules Farné had failed miserably in his duty as a gentleman, but no foul play had been proven, and, above all, the search had yielded no body.

Silently, and under the withering stare of the Constable, Jules Farné was released from the cells in the early hours. All eyes were on him, following him down the street, waiting for an opportune moment to intercept him. So, he sprinted down to the docks and fled on the first ferry to France, just one step ahead of the wolves.

Public interest, verging on hysteria, remained high. A letter to the British Press and Jersey Times lamented that laws on prohibiting skiffs to roam outside the harbour would be somewhat fruitless “in these liberty-loving days”. Yet Victorian ingenuity and practicality offered a better way: the writer proposed “an efficacious remedy… every scull must have a lanyard made fast to it just inboard of the rowlock. By this simple arrangement, an oarsman could never lose his sculls, even if he tried to”.

Truth to tell, few had come out of this tragic episode with much credit. The young ladies had been foolishly naïve; the Frenchmen reckless albeit not criminally culpable; the boat-owner rather too keen to pocket coin on the Sabbath. Much criticism also centred on the shockingly sluggish speed of the official rescue operation. It was a full day before the Duke of Normandy tug boat steamed round the coast, hunting for signs of a rowing boat, or timber wreckage, or a sea-bloated body.

All efforts failed; every search drew a blank in the vast labyrinth of the seas. In desperation, soldiers dynamited the sea-bed between the piers, but the muffled explosion dredged up only a tangle of fishing nets and some timbers from an old wreck. There was no sign of the young lady who had rowed here at twilight on Sunday evening. Louisa had been swept off the face of the Earth.

Prayers went unanswered; headlines moved on. In Elder Cottage, grief festered deep in the bone. The weeks slid by. And then came a knock on the door. An urgent telegram had arrived, from across the face of the globe.

Louisa’s Story

Crown Colony of Newfoundland

God rescued me, and I will never know the reason why. I was no Grace Darling, giving up my brave life to save mariners. I was certainly no Nightingale. I was just a foolish, reckless girl. I had spent my last breath of hope, and accepted my inevitable fate, when I first saw that ship steaming towards me. I had no strength and no voice left; I had only my sodden pocket handkerchief to wave. It was enough.

As if in a dream, the great vessel came alongside and threw me a rope, but I was far too weak to grab it and the ship sailed on by. Tombold of St Malo, its stern proudly read; a French Atlantic steamer.

So, the sailors turned back and rescued me. They carried me like a child, deep into the bowels of their ship. Captain Edouard Landgren, my hero, my second father, had saved my life. He ushered me to a modest cabin and to me it was as welcome as a royal palace. He offered me a set of his own clothes, which were mercifully dry if (I confess) hardly flattering for a twenty-two-year-old lady! He plied me with sweet cider (which I refused) and strong hot tea (which I lapped up); but I soon collapsed into a deep and dreamless sleep. I woke to find the cabin lurching like fury around me. Soon after they found me, the ocean had erupted into a savage storm. I had been plucked from the maw of the beast.

The violence of the weather prevented any hope of return; we were unable to change course but ploughed on for some two thousand three hundred miles across the Atlantic. The voyage was long and bitter; some three weeks into the journey, one sailor was swept overboard and drowned in the deep. Yet the French sailors treated me ever so kindly, as if I was an honoured princess aboard their ship. Twenty-six long days and nights later, the shores of the North American continent hove into view, sheer cliffs shrouded in a thick peasouper that reminded me very much of home.

They tried to moor in the French fishing grounds of St Pierre and Miquelon, but the fog prevented it. So, they ducked in to the tiny fishing harbour at St George’s, where the Rev Jeffrey and his wife welcomed me in. The sun burst through at noon. As fate would have it, it was another beautiful Sunday afternoon when my rowing expedition across the Atlantic Ocean finally came to its appointed end.

And so today I am seated in a small bureau in St John’s, the colonial capital of Newfoundland, observing a most curious and beautiful device. It is an incredible instrument, resembling a piano keyboard, but with twenty-six keys, one for each letter of the alphabet. Spinning behind it is an electric motor and rotating mechanical drums, like some mesmeric creation from a Jules Verne novel. They say an undersea cable runs from this very room, thousands of miles across the ocean to Valentia Island in Ireland, thence to London, and finally over to Jersey. It feels like an umbilical cord calling me home. The Colonial Secretary has ordered a telegram to be sent to the office of Her Majesty Queen Victoria herself.

This is the machine that sent my incredible story to the other side of the Earth. This is the device that told my Father that I am alive. Now it will tell my family that I am coming back soon, across the great divide, and that soon enough I will see their faces once again. Before the summer is out, I will stand on Jersey soil.

The machine is ready now, whirring with the strange power of electricity, pulsing with the hope of tomorrow. Then the operator reaches for the keyboard, and silently begins to tap my message home.

Louisa Journeaux was safe; a survivor who had endured the raw power of the ocean and had lived to tell the tale. Captain Landgren was feted and presented with a gold medal at the Town Hall, but Louisa shunned the attention. She settled down to a conventional life, working in a draper’s store in St Helier, and she would live to a ripe old age.

Thank you for reading. This story is taken from my second book, Jersey: Secrets of the Sea, which is available from Amazon, Waterstones in Jersey, WH Smith and the Harbour Gallery.

© Paul Darroch 2025.

Music - Chariots by Gavin Luke. Courtesy of Epidemic Sound.